The Inflationary Decade

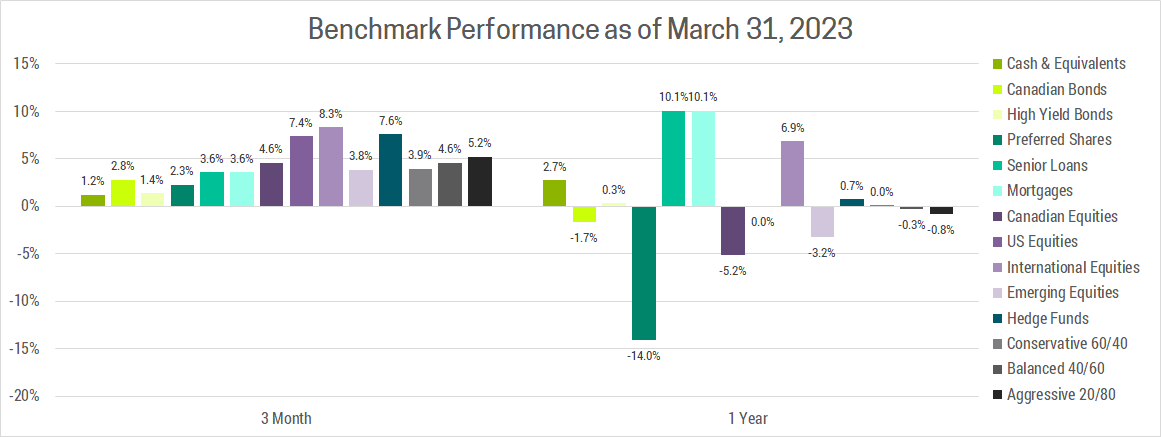

Easing inflation and resilient economic growth allowed markets to continue the recovery that began in Q4. While the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was a temporary setback, most major asset classes still ended the quarter higher.

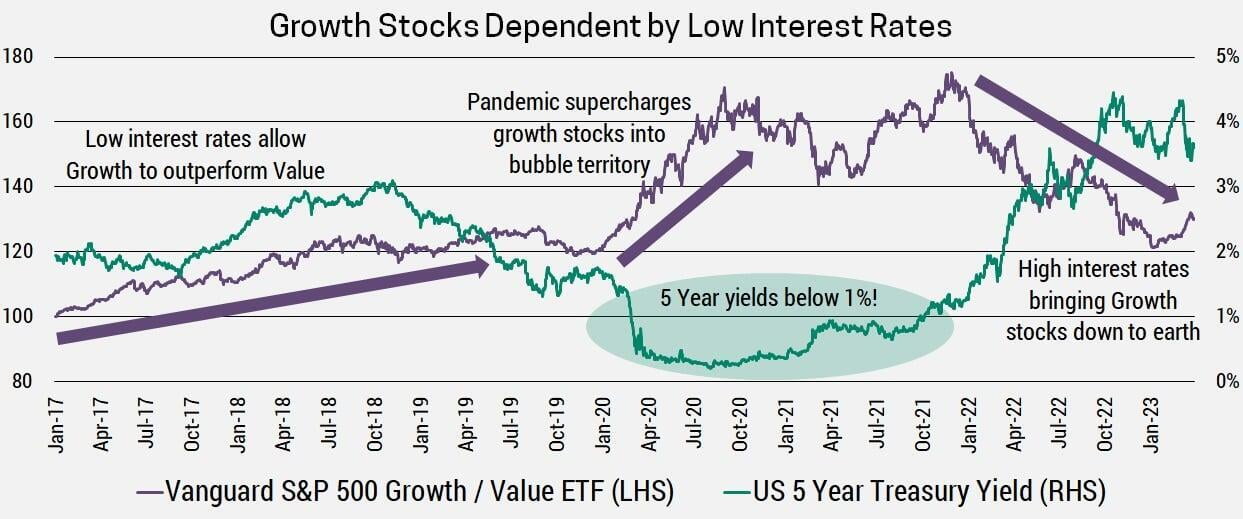

Rising interest rates have already burst the bubbles in cryptocurrencies and innovation stocks, while taking the froth out of expensive growth stocks and real-estate. With the collapse of SVB, this trend has begun to reverse. The consensus believes that central banks can’t continue to raise rates when each time they do so another part of the economy breaks. As a result, markets think interest rates have peaked and are now expecting rate cuts before year-end. This is why the most interest rate sensitive portions of the market have started outperforming again.

We fundamentally disagree with this view, as we believe the low-growth, low-inflation environment that prevailed last decade as an anomaly. To understand why, we will revisit the circumstances that gave rise to the deflationary 2010s and contrast that with our current environment.

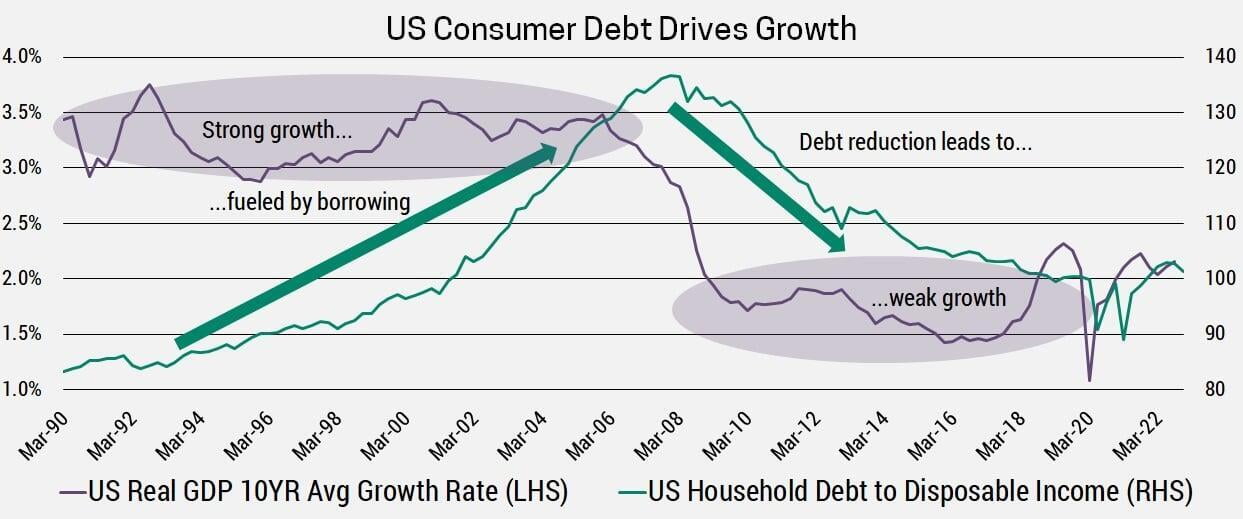

The subprime crisis of 2008 caused the US housing market to burst and ever since Americans have been paying down their debt. Europeans followed due to the sovereign debt crisis in 2011. As a result, the two largest economies at the time were deleveraging last decade, which means less money going towards consumption (i.e. less demand). Meanwhile, supply was robust as globalization was in full swing. We hadn’t yet seen the days of trade wars and military conflicts that has caused countries to lose trust in each other. This sparked the new trend towards domestic and diversified manufacturing in the pursuit of supply chain resiliency, instead of efficiency.

The Fed and ECB (European Central Bank) sought to stimulate demand by dropping interest rates to 0%. Unfortunately, this did not have the desired effect. Recent memory of the perils of debt kept consumers from borrowing and banks from lending recklessly. Demand was weak and supply chains were robust, so it’s really no surprise the 2010s saw prices stagnate.

Outside the US and EU, the remainder of the global economy (including Canada), took advantage of low interest rates to add to their existing mountains of debt. Central banks worldwide were forced to drop interest rates in-line with the Fed and ECB to avoid having their currencies appreciate. After all, when investors own a currency, they are compensated based on interest rates. A higher rate in one country incentivizes investors to hold that currency, which causes it to appreciate. Had Canada (and others) kept interest rates high last decade, their currencies would appreciate causing exports to look relatively more expensive to their trading partners.

Unfortunately, keeping interest rates near 0% for a decade had some unintended consequences. It caused massive appreciation in real-estate, long-term bonds and speculative investments like cryptocurrencies, innovation/tech and growth stocks, among others. This trend was already well underway when the pandemic struck, which caused central banks and governments to pump even more money into the economy, turbocharging asset prices into bubble territory.

The current environment is shaping up to be the exact opposite of last decade. The US and EU that act as global price setters are finished deleveraging. Furthermore, China which surpassed Europe in 2021 to become the second largest economy is rebounding after lifting their zero-COVID strategy. As such, the three largest economies have growth rates and inflation running at a much higher level than last decade, justifying much higher interest rates that overly-indebted countries like Canada simply can’t cope with.

The Bank of Canada knows the risk high interest rates pose to over-indebted consumers and our real-estate market, unfortunately they are stuck between a rock and a hard place. Failing to keep up with global interest rate increases would result in a falling CAD, which increases import costs and exacerbates an already crippling inflation problem. In the end, over-indebted economies like Canada are likely in for a decade long deleveraging cycle, similar to what the US and EU experienced last decade.

To summarize, the US and EU are the largest global consumers, so they act as price setters. Last decade, they were the weakest economies, so global interest rates were held near 0% to help stimulate demand and lift us out of deflation. This decade the US and EU are amongst the strongest economies, so global interest rates will need to be sustainably higher to curtail demand and tame inflation.

Outside of your portfolio, we mentioned in Q1 2023 that it now makes sense to prioritize debt repayment, particularly if the interest rate exceeds 6%. Since then, the collapse of SVB has caused interest rate forecasts to drop, which gets priced into fixed-rate mortgages. This provides variable rate borrowers with a temporary lifeline on mortgage rates. Spring tends to be the most active time in the real-estate market, which means 5-year fixed mortgages are most competitively priced. If you’re struggling to make your current payment, you need to consider locking in a 5-year fixed or downsizing, as you cannot rely on falling interest rates to bail you out.

If you have any questions, comments or would like to become a client please do not hesitate to reach out. You can email us or schedule a free 30-minute consultation using the link below.